Moridja Kitenge Banza – Top Contemporary Art Stories by Horcelie Sinda Wa Mbongo.

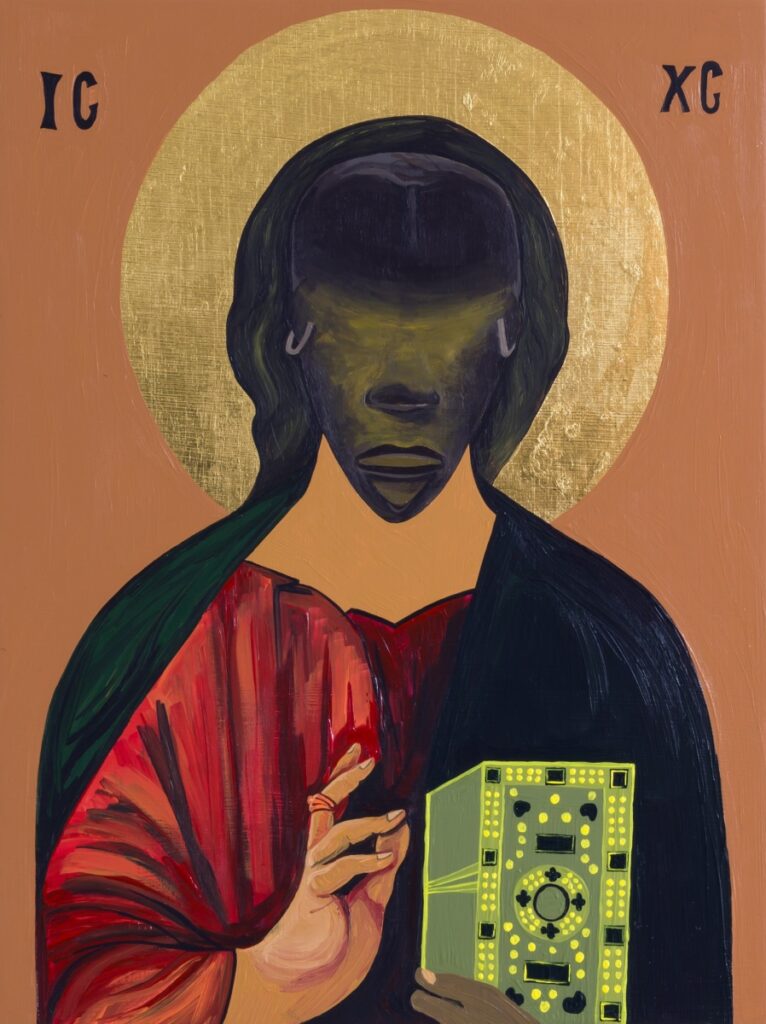

Between the still and moving image, the representational and the non-representational, Congolese born artist, Moridja Kitenge Banza’s merge of dimensional mediums form the political and cultural dialect of the Congolese body. Each body of work echoes the closeness and distances of colonisation of his generation. For Banza, he is a generation not directly connected to slavery but colonisation. His great-grandchildren may be the ones who will be further away from the colonial ideologies. They will also be the ones to continue telling the history of the Congo. In discussing spirituality and religion, Banza’s portrayal of the painting Christ, in the painting Christ Pantocrator, combines traditional religious layers of Congolese beliefs with Christianity. Banza explores how both paths have influenced his identity. The influence arose when he was given the bible from his father before taking on France’s journey. With this painting, Banza attempts to fuse the Congolese body before and after colonisation. The tales of identity in the Congo were created in pain; Christ Pantocrator is a tale which depicts how the tale of the Congolese identity became apparent.

“If I had never taken interest in art I would not have taken interest in going to the museum.”

Hymne a nous; through the conceptual a memory

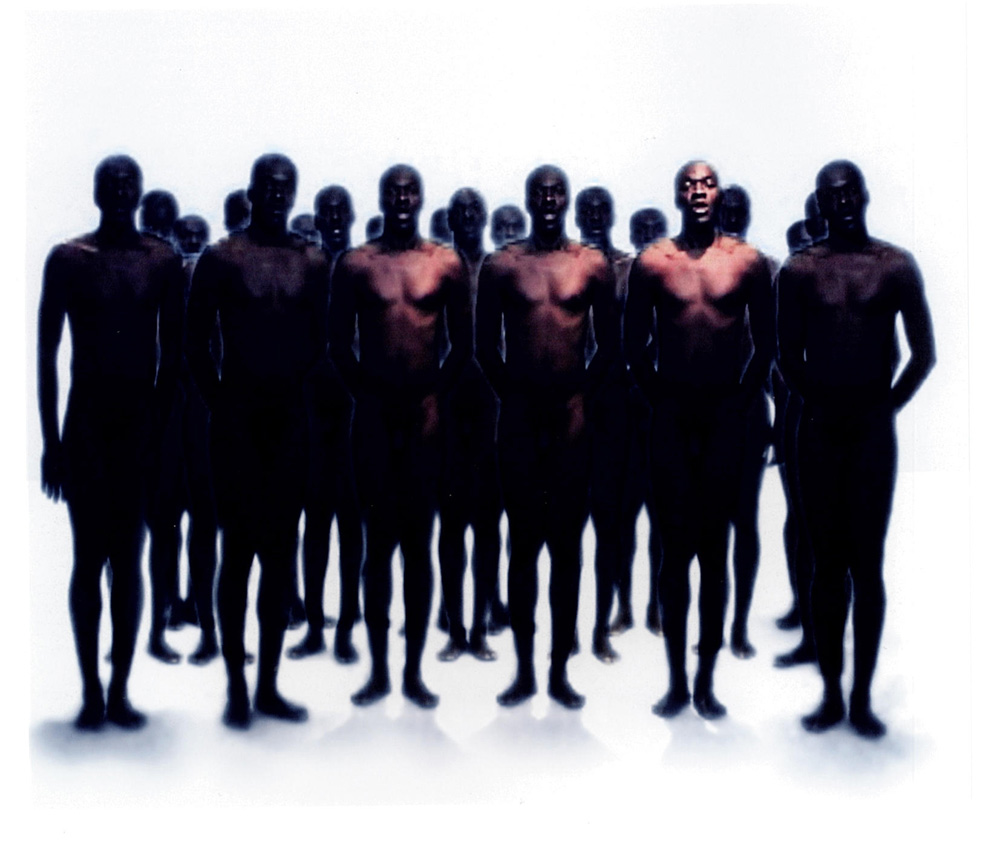

Besides the Congolese body of the past, other video installations such as El Dorado explore the false tales the Congolese tell others when they return to Congo. The complex of colonisation amongst the Congolese has created beliefs, which result in the community to remain in poverty. Upon arrival, Banza discovered these falsehoods also existed within African communities. Many of the African position themselves as more important than those who live in Africa. The video is like an interview in which performers discuss their work experiences. Upon the gaze, the viewer becomes the interviewer questioning and listening. Banza included performers of different ethnicities to demonstrate and expand on the difficulty of living in a foreign country. The body of work is a visual analysis of the challenges immigrants face, seeking a job based on their education level. Often when living in these spaces, immigrants discover their qualifications are irrelevant, in which modernisation has created slaves out of the foreigners. The body of work addresses these realities in which one may become the” other”. The camera in El Dorado is a mirror in which the performer perceives their fears and hopes of a better life. As one watches, It is as though their gaze determines whether or not they are qualified.

Moreover, Banza sought his viewers to seize the video’s multi-layers. It challenges the discussion of immigration and integration. For Banza one’s attempt to succeed as a foreigner may fail, but what they choose to do after their failures can change many things.

The Congolese body’s concept in moving images evokes a hymn of nationalism and interpretation. In work, Hymn a Nous Banza’s nude body performs a contextualised hymn vocally, infused with the Congolese and Belgium’s national anthem, poem by Schiller and a fabricated text by King Leopold. According to Banza, each text constitutes the multiple layers of his identity. The notion of a chorus is to chant and re-compose the layers of history. The vocals are conceptualised to echo the affirming plurality of the self.

Why did you decide to continue to pursue art despite the challenges of citizenship?;

M.K.B: I received a scholarship to study in France for five years, which allowed me to expand my knowledge about art. Initially, I wanted to study abroad, get a diploma and return to teach at the Academy des beaux-arts in Kinshasa. I later decided to stay in Canada because my objective was to accomplish my “whys” and pursue a career in the arts. Canada was the best place to stay because I could receive permanent residency after eight months. I continued to pursue my career in the arts because of my objective to succeed as an artist. I thought to myself, even if I do not succeed as an artist I will seek a job in the arts.

How can the Congolese Museum or galleries transform the way of representing art?

M.K.B: Museums are a western concept, so the word Museum does not exist in Congolese languages. However, how can we (Congolese) align and transform such concepts into their culture? Moreover, how can we create museums that are not replicate in western museums? The notion of a museum is to conserve historical artefacts. In the Congolese culture, the idea of a museum is theatrical and oral, in which we call ‘Masolo”. Our grandparents, wise men and women are the ones who conserved history. We are an oral culture, but we tend to copy European culture, and we forget to introduce the oral element. I introduced the oral concept in one of my artwork Griot, 2018, exhibited in a library in Canada. I try to incorporate what I have learnt from my Congolese heritage and adapt it to the realities I encounter.

Installation (Berlin)

Banza was awarded Canada’s most prestigious contemporary art prize in 2020, In 2010, he was awarded the first prize of the Biennale of Contemporary African Art Hymne a nous.

Moridja Kitenge Banza – Top Contemporary Art Stories by Horcelie Sinda Wa Mbongo.

No products in the basket.

No products in the basket.