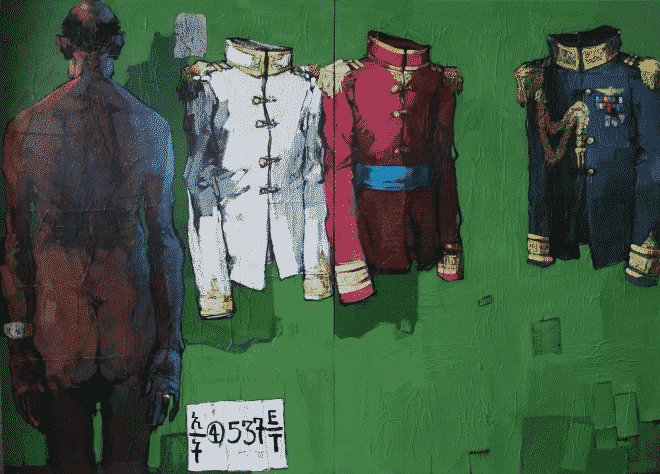

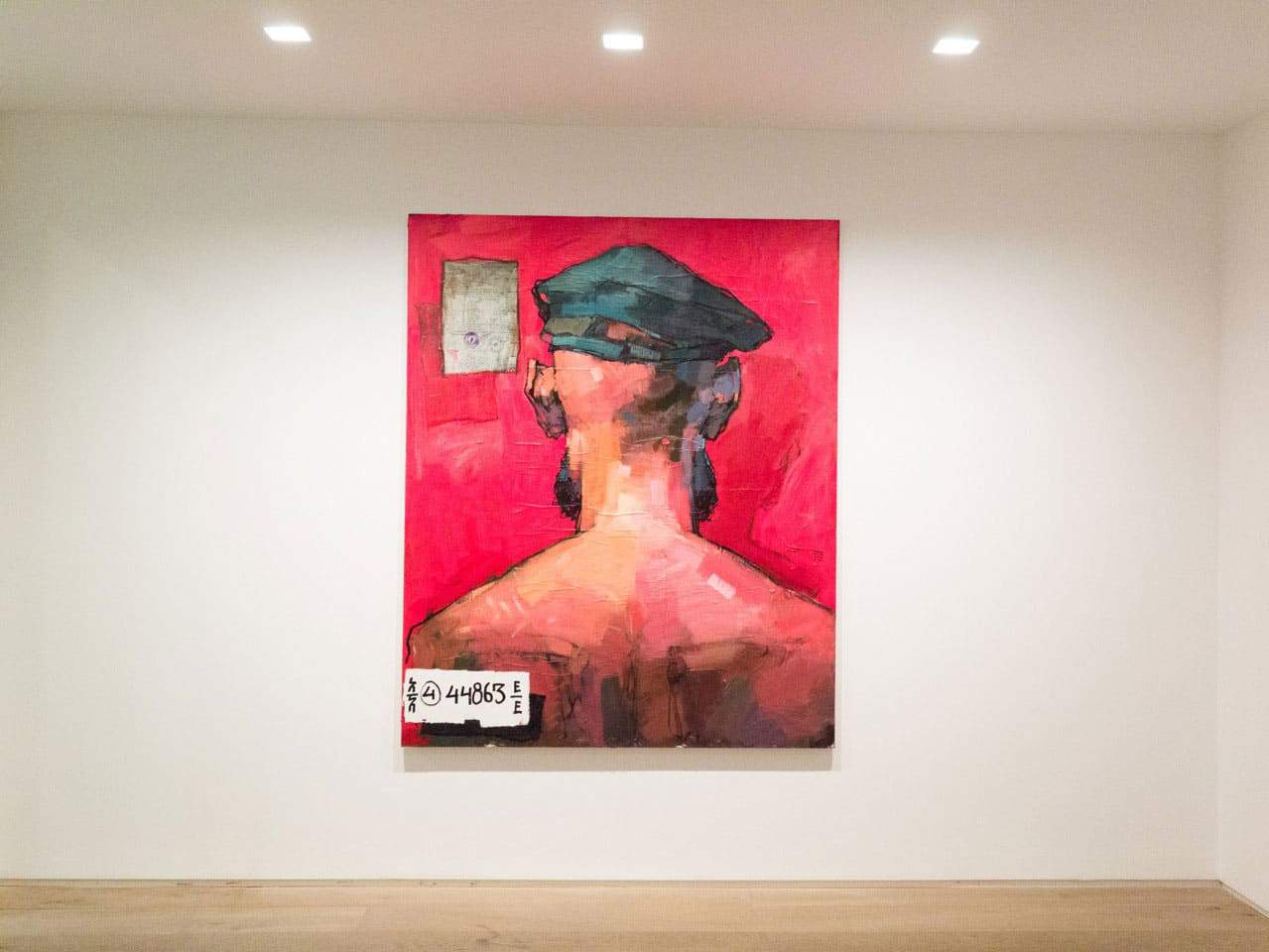

Contemporary Art Challenges Ethiopia – Walls, domes and the exteriors of the magnificent Medhane Alem Cathedral in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa are embellished with colorful portraits and life-size paintings of saints of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The saints, depicted with an exaggerated size of eyes, solemnly gaze at visitors and worshippers who congregate throughout the week.

Bekele Mekonen, an academic at Addis Ababa University’s Alle School of Fine Arts and Design, says religious paintings which began with Christianization of Ethiopia in the 4th century uniformly adopted a style of depicting the eyes of their subjects bigger than their normal size to “hypnotize the viewers”.

“The philosophy of the style is that it is not only the viewer who look at the paintings, but the paintings also observe the viewers,” Bekele noted. According to Mekonen, despite centuries of artistic tradition and nearly a century of education, the secularized and westernized contemporary Ethiopian painting and sculpture are “in dire straits”. “Today, the art community and academia also have big eyes which are engaged in mesmeric stares at the problems of Ethiopian painting and sculpture,” Bekele noted.

‘Mesmeric stare at problems’

The ancient religious paintings constitute a unique visual history and form of teachings of the church, Mekonen said. From an artistic point of view, some notable Ethiopian contemporary painters had adopted specific elements of style in religious paintings, he added. According to Mekonen, despite centuries of artistic tradition and nearly a century of academic trainings, the overall level of contemporary painting and sculpture was abysmally low. “One of the most fundamental problems lies in societal and institutional attitudes as well as lack of knowledge in the significance of paintings and sculpture,” he noted.

“For some, these art forms are luxury and play no role in the material and spiritual development of our society,” Bekele lamented. According to him, such attitudes have negatively impacted the expansion of government and private academic institutions.

“We hope this would change in the future, but currently the aesthetic test of our society is very low,” he said, adding: “Despite some great works in the past, the overall artistic quality of paintings and sculptures is not up to the aspired level.” Mekonen, also a renowned sculptor, noted that as sculpture requires space, it was difficult for aspiring young artists to have their own studios. Mekonen added: “Besides, as Ethiopia is a profoundly religious society of Christians and Muslims, both religions associate sculptures with idolatrous worship, and viewers, buyers, and ‘would be’ artists are virtually disinterested.”

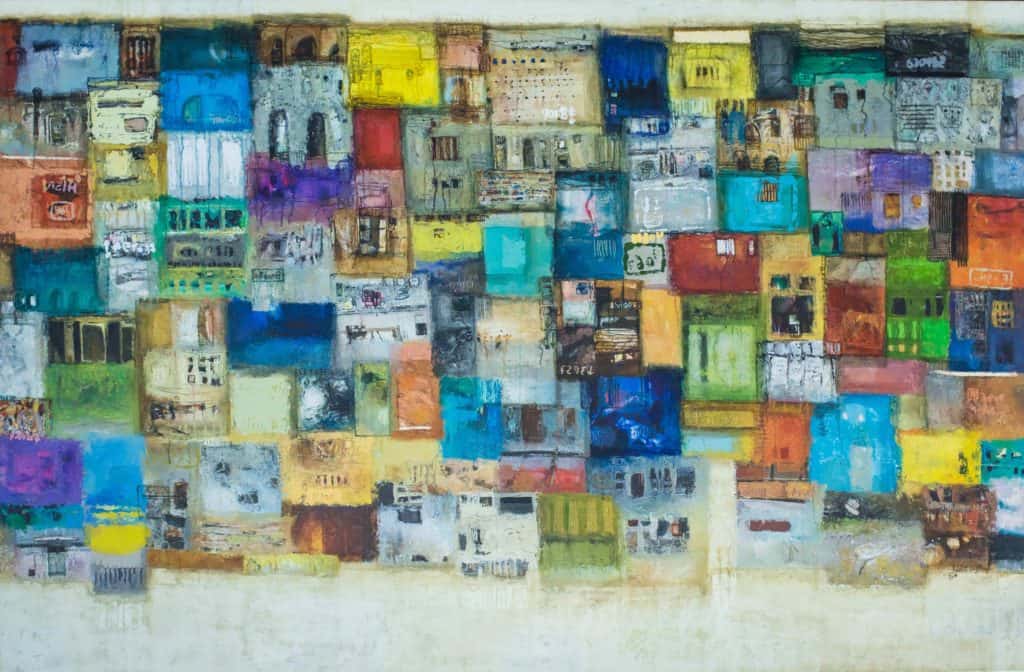

Mifta Zeleke, a curator, told Anadolu Agency that one of the factors that impeded the growth of art was the self-serving attention given by successive Ethiopian governments to the profession. The governments get the painters engaged only when they require propaganda posters, paintings and sculptures, he said. Zeleke added: “The country’s cultural policy does not provide ways and means for the development of the field.” Consequently, Ethiopia has very few galleries, curators, and art critiques, according to Zeleke. “We need to solve our problems to get near enough to African art capitals — Accra, Dakar, and Johannesburg, among others,” he added.

No products in the basket.

No products in the basket.