BRUSSELS—A push to return African artworks from museums in Europe and America to their original countries is gaining traction. But it’s raising complex and sometimes uncomfortable challenges.

For years, sub-Saharan Africa’s missing art—much of which was looted during wartimes and ended up in collections across the globe—didn’t attract the level of attention devoted to higher-profile campaigns, such as Greece’s efforts to wrest the Elgin Marbles back from Britain or Italy’s tussles with California’s Getty museum. Now new advocates are advancing the cause of African art.

Late last year, a report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron called for France to repatriate African artwork taken without consent during the colonial era, if the countries of origin ask for them back. More broadly, African cultural groups are putting pressure on governments to return disputed art. And a well-connected Congolese businessman is on a mission to track down works that disappeared from an Angolan museum during the country’s civil war.

For European and American museums that hold disputed works, it can be a difficult conversation. “Most of the museums are of the view that something must change, but they don’t know exactly what and how much to change,” said Lawrence Oduro-Sarpong, chairperson at AfricAvenir International, a nonprofit that promotes African cultures and is pushing for the return of looted objects and artifacts.

“The financial aspect is what is making some people in power reluctant to admit or recognize anything: If they return objects, they’re admitting that they were unlawfully here. Then other claims may come, like rent,” Mr. Oduro-Sarpong says. “Somewhere along the line there must be a first step.”

A new museum set to open in Congo’s Kinshasa before the end of the year is highlighting some of the challenges. In Belgium’s Royal Museum for Central Africa, about 85% of its 125,000 ethnographical objects, which include everyday items like bowls and arrows, come from Congo. About 10% of those would be considered works of art, like carved wooden masks and statues, estimates Guido Gryseels, director general of the Belgian museum.

He says he has had informal discussions with Congolese officials and that the museum would be open to returning some disputed items and lending back others. “We need to facilitate access to those collections,” he says. In particular, he says he’s open to discussing the return of a few prized pieces as a show of goodwill, as well as objects proven to have been stolen during military expeditions or raids, of which Mr. Gryseels estimates there are fewer than 1,000.

But a major issue is that many of the works in the Royal Museum’s collection were acquired and brought back to Belgium by missionaries: “What were the conditions of the exchange?” Mr. Gryseels said. “That’s the most difficult part.”

Despite the informal talks, the Belgian museum so far hasn’t received a formal request to return any objects, Mr. Gryseels says. “The Congolese officials have said to me on several occasions they don’t want restitution as such—what they do want is to have a more representative sample,” Mr. Gryseels said. The Congo museum and government officials couldn’t be reached for comment.

Other campaigns have yielded some tangible successes. In Brussels, the Bozar fine arts center is staging an exhibition that includes two pieces set to return to Angola’s Dundo Regional Museum after the show. The pieces had been tracked down by prominent Congolese collector Sindika Dokolo, who recovered them from private collections and then lent them, along with other artwork, to Bozar for the show.

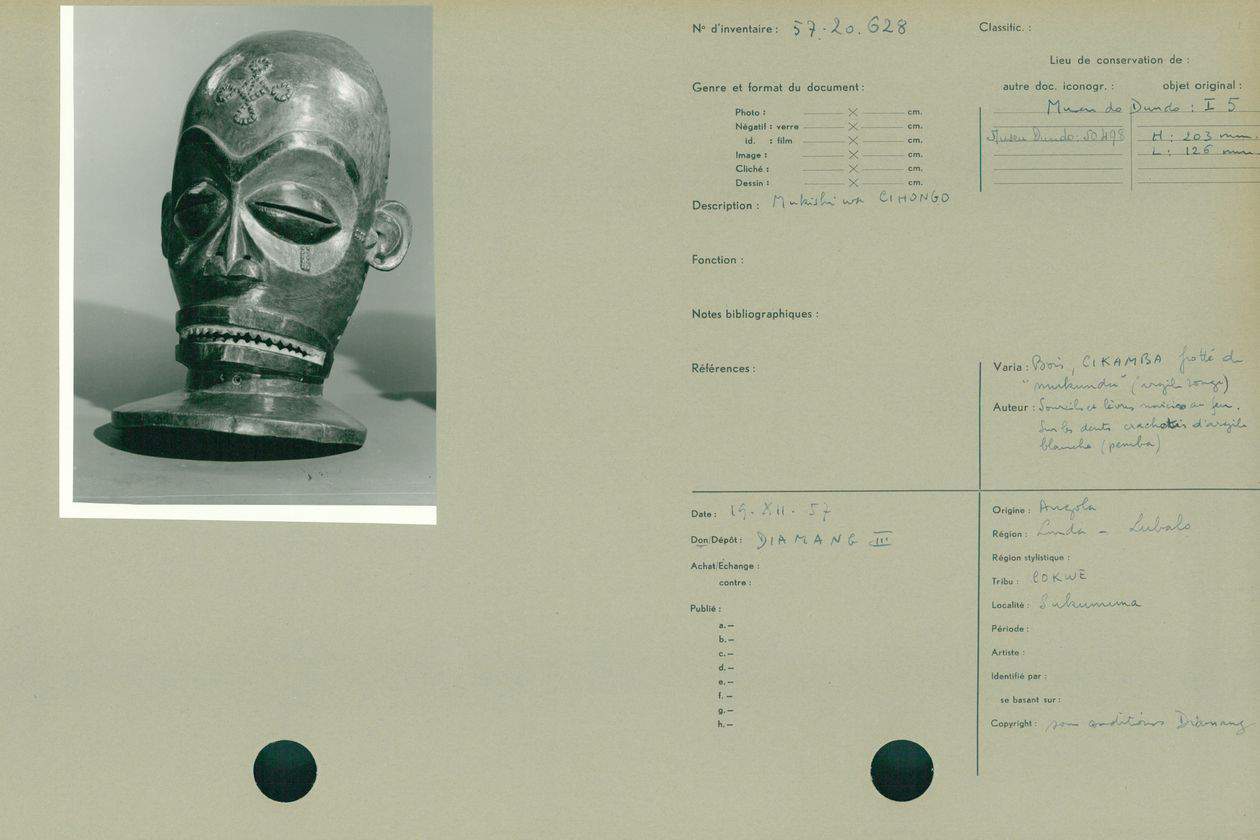

Mr. Dokolo is waging a broader campaign to recover and return African artwork. A well-connected businessman, he is married to Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of former Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos and one of Africa’s wealthiest women. Mr. Dokolo says he has found and purchased 15 pieces so far that he intends to return to the Dundo museum, including the two on display at Bozar. He says he typically confronts the current owners with evidence that a piece was stolen—usually museum inventory cards that describe and depict the work. Then he makes an offer: “They need to show me what they paid and I pay them back what they paid for it—which is not the market price—because it’s a stolen object,” Mr. Dokolo said. “If they refuse to sell, my lawyers go after them. It’s worked a few times.”

Bring African Art Home

The Brussels exhibition calls attention to other works that are still missing from the Angolan museum—items believed to have disappeared during the country’s civil war. One room features photographs of cards that describe missing items such as masks, statues and flywhisks. The exhibition’s curator hopes the spotlight will put pressure on the collectors who now hold these pieces. “The large images on the wall are in known Belgian collections,” says Kendell Geers, a South African artist and curator of the exhibition, called IncarNations. “[The collectors] can do the right thing now quietly, or we can also put their names on the wall…that would be the next step.”

In the U.S., at least one museum has successfully returned works to their country of origin. In July, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science gave a collection of 30 wooden grave markers to the Nairobi National Museum in Kenya.

The markers had been donated to the Denver museum in the late 1980s or early 1990s, says Steve Nash, director of anthropology and senior curator of archaeology at the museum. He says the statues never really fit into the museum’s collection, and had never been displayed. The museum was uncomfortable with the idea of holding the items: The community in Kenya that the markers came from believed they embodied a dead person’s spirit or soul. “We think curating somebody’s spirit is not a good idea,” says Mr. Nash.

He says the museum had to navigate through Kenyan bureaucracy for over a decade, but eventually was able to return them. He does worry the statues now will suffer deterioration, since they’ll be outside reinstalled on gravesites, where they’re meant to be. “As a museum curator, I can say, ‘Oh my God, what’s going to happen with these things?,’” Mr. Nash said. “But they were stolen. Everything else that derived from that act was null and void.”

Seeking Returns

Since the early 1980s, Greece has been trying to bring home the famous sculptures known as the Elgin Marbles, which the country says were looted from the Parthenon’s frieze on the Acropolis two centuries ago by the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Thomas Bruce, the Seventh Earl of Elgin. The sculptures, on display at the British Museum in London since 1817, are perhaps the most famous example of a country seeking the return of its cultural heritage.

The Trustees of the British Museum believe that the “sculptures are part of everyone’s shared heritage and transcend cultural boundaries,” the British Museum writes on a section of its website dedicated to the controversy. “The Trustees remain convinced that the current locations of the Parthenon sculptures allows different and complementary stories to be told about the surviving sculptures, highlighting their significance for world culture and affirming the universal legacy of ancient Greece.”

Not all battles have been so lengthy. In February this year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York returned a gilded coffin to the government of Egypt, after learning that the coffin had been looted from the country. The Museum had purchased the coffin in July 2017 after vetting the purchase. The museum said it would review and revise its acquisitions process.

“After we learned that the Museum was a victim of fraud and unwittingly participated in the illegal trade of antiquities, we worked with the DA’s office for its return to Egypt,” Daniel Weiss, the Met’s president and chief executive, said in a statement at the time. “We extend our apologies to…the people of Egypt.”

This …Bring African Art Home … article is by Alexandra Wexler and originally posted on the WSJ.

No products in the basket.

No products in the basket.