In Why Do We Need An Art Fair Dedicated To African Art? Rebecca Anne Proctor asks Will African contemporary art need to be viewed in isolation as it becomes more mainstream? Gallerists, collectors and curators respond during the recent edition of 1-54 London

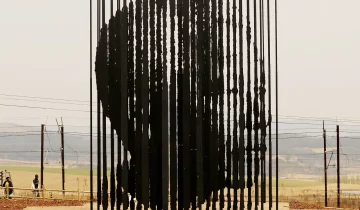

Stationed inside the outdoor courtyard of London’s Somerset House defined by its prominent neoclassical architecture are the bold forms of Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda’s monumental structure The Fortress (2019).

Kia-Henda is the recipient of the 2019 sculptural commission for 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, awarded each year to an artist from the African continent. His sculpture combines urban materials with ancient ruins to reveal the structures of a city – a metaphor for what “Fortress Europe” once meant.

Represented by South Africa’s Goodman Gallery, Kia-Henda’s sculpture is from his A City Called Mirage series, commenting on how the cities and the fortresses that protect us are now a perversion speculated upon for profit. After 1-54 the sculpture travelled to the ancient village of Utique in Tunisia where the Kamel Lazaar Foundation, which has entered into a multi-year sponsorship of 1-54’s sculpture commission, has its Sculpture Park.

Tunisia is an apt location for Kia-Henda’s work. The country has long served as the Launchpad for many migrants’ journeys in search of what the artist calls the “European mirage.”

During a time when the world continues to grapple with how to handle the repercussions behind these so-called “mirage journeys” as well as the socio-political scars left from centuries of colonial rule, since 2013 the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair has provided a platform for art from the continent and its diasporas to be seen and heard. Now with annual editions in London, Marrakech and New York, and run by the fair’s founder and director Touria El Glaoui, the fair demonstrates the increasing appetite for African art.

The London edition witnessed over 18,000 people over five days and displayed the work of 45 galleries from 19 countries, 15 of which exhibited at the London fair for the first time, and more than 140 African and African diaspora artists.

“The buzz surrounding art from Africa and the diaspora across the London this year has been especially strong with the opening of South Africa’s Goodman Gallery and the wonderful Kara Walker commission for the Tate Modern Turbine Hall and we are so proud to have been a part of it,” says El Glaoui.

In one of Somerset House’s connecting rooms was the haunting work of South African artist Mary Sibande. Incorporating installation and photography, the show, Mary Sibande: I Came Apart at the Seams (through 5 January 2020), explored the construction of identity in postcolonial South Africa. The exhibition, in collaboration with Somerset House, marked the fourth time that 1-54 had staged a show extending beyond the fair week. Last year’s exhibition was dedicated to the work of Hassan Hajjaj.

This year, the 1-54 FORUM was curated by Head of International Collection Exhibitions at Tate, Kerryn Greenberg, and was dedicated to the late Nigerian curator Bisi Silva who championed women artists and experimental artistic practices.

While most galleries reported sales, one anonymous gallerist commented that there seemed to be more “action” at Frieze London and how the mood of impending Brexit seemed more evident at 1-54. “There was a lackluster spirit and the works weren’t as high in quality as in previous years,” he said. “Everyone worried that Frieze would be affected by Brexit, but it was at 1-54 that I felt the changes and it is 1-54 that offers work at a lower price tag.”

On the flip side, Vigo Gallery had a strong fair, selling 56 of Ibrahim El-Salahi’s small pain relief drawings as well as several of his larger canvases from the same series. First time participant SMITH from Cape Town sold out their booth. On day one New York’s James Cohen Gallery sold two Yink Shonibare artworks for $16,000 and $85,000. Accra’s Gallery 1957 sold Ghanaian-British artist Godfried Donkor’s Olympians XV for £20,000. Cape Town’s SMAC Gallery sold Cyrus Kabiru’s Macho Nne: The Honeycomb and Mary Sibande Turn, turn, turn, turn (Prices on the booth ranged from £8,000 – £12,000).

“1-54 this year was one of the best fairs we have done,” said London and Berlin-based Kristin Hjellegjerde. “We sold multiple artworks by four of our artists: Gerald Chukwuma, Dawit Abebe, Nengi Omuku and Ephrem Solomon in the range of $8.000-$22,000. We sold 16 artworks plus stock.”

“This is the century for African art,” she continued. “It’s fresh, touching and with strong narratives—the work that is being presented has soul. I feel blessed to be part of this revolution.”

Addis Ababa and London-based Addis Fine Art sold several works by painter Merikokeb Berhanu for between £7,000 and £15,000; four works by Tadesse Mesfin for between £25-35,000; and four works by Brussels-based Ethiopian artist Ermias Kifleyesus for between £5,500 and £12,500.

Dubai and London-based Lawrie Shabibi sold Zak Ové’s Hands Up sculpture to a major North American Museum and sold out paintings by Fathi Hassan.

Successes abound with a wealth of art on display, the question on everyone’s lips was what will happen to 1-54 in the future as African art becomes more mainstream? Will there even be a need for a specialised fair dedicated to art from the continent?

“When 1-54 began it was necessary to create a platform solely committed to the continent,” says El Glaoui. “I wouldn’t say we were isolating it, but giving it a much-needed space that let it challenge the international art scene and the dominant discourses that excluded it for so long.”

“I think and hope that niche fairs like 1-54 will have to evolve to normalise what is normal and won’t need to isolate African Artists and dealers to get noticed,” said curator Azu Nwagbogu. “Exporting art through geography is thankfully becoming increasing more redundant but for now it is serving a useful purpose.”

Yet how do we define what is normal today in a world where cultural centers continue to shift and the discourse du jour focuses on identity politics and post-colonialism – even under the iconic white tipped tents of Frieze London?

“No, I think in the future there won’t be a need for a separate fair for artists from the continent and diaspora,” says Jane Cohen of New York-based James Cohen Gallery that represents a growing roster of African artists.”

“For the past two years, we’ve participated in New York and London [1-54]. We along with our gallery artist Yinka Shonibare CBE decided to support Touria El Glaoui because we are very impressed with what she has been able to accomplish.

We share her belief that the artists shown at 1-54 need an international platform and their voices need to be represented in the larger discussion of contemporary art.”

This year marked London-based Tiwani Gallery’s debut in the Focus section at Frieze London 2019 with a solo presentation by British-Nigerian artist Joy Labinjo. The gallery has exhibited at 1-54 since the fair’s inception.

“I think our decision to participate in both fairs is proof of what [the art world] has been expressing up until now: artists from African and its Diaspora blur boundaries,” says founder and director Maria Varnava. “Our participation in both fairs is similar to that blurring of boundaries.”

“I think there will always be a need for a platform like 1-54 because there are more galleries on the continent that now want to be part of it and I would assume more galleries will also come into existence,” she added.

“I do not consider 1-54 to be a fair placing African artists in isolation,” says Rakeb Sile of Addis Fine Art. “It’s a dedicated space to explore the diversity and quality of art across a vast source of artistic production.”

As the winds shift, new narratives are written and change settles in. Adaptability is key. “As ever, we’re not afraid to bend and re-imagine the art fair model to ensure we continue to be adaptable and sustainable for all,” adds El Glaoui. “We pride ourselves on being adaptable and reactive. It is vital that we are. We are a platform dedicated to the artists of an entire, incomprehensibly diverse continent and its expansive diaspora.”

Why Do We Need An Art Fair Dedicated To African Art? is taken from HarpersBazarArabia and is written by Rebecca Anne Proctor

No products in the basket.

No products in the basket.